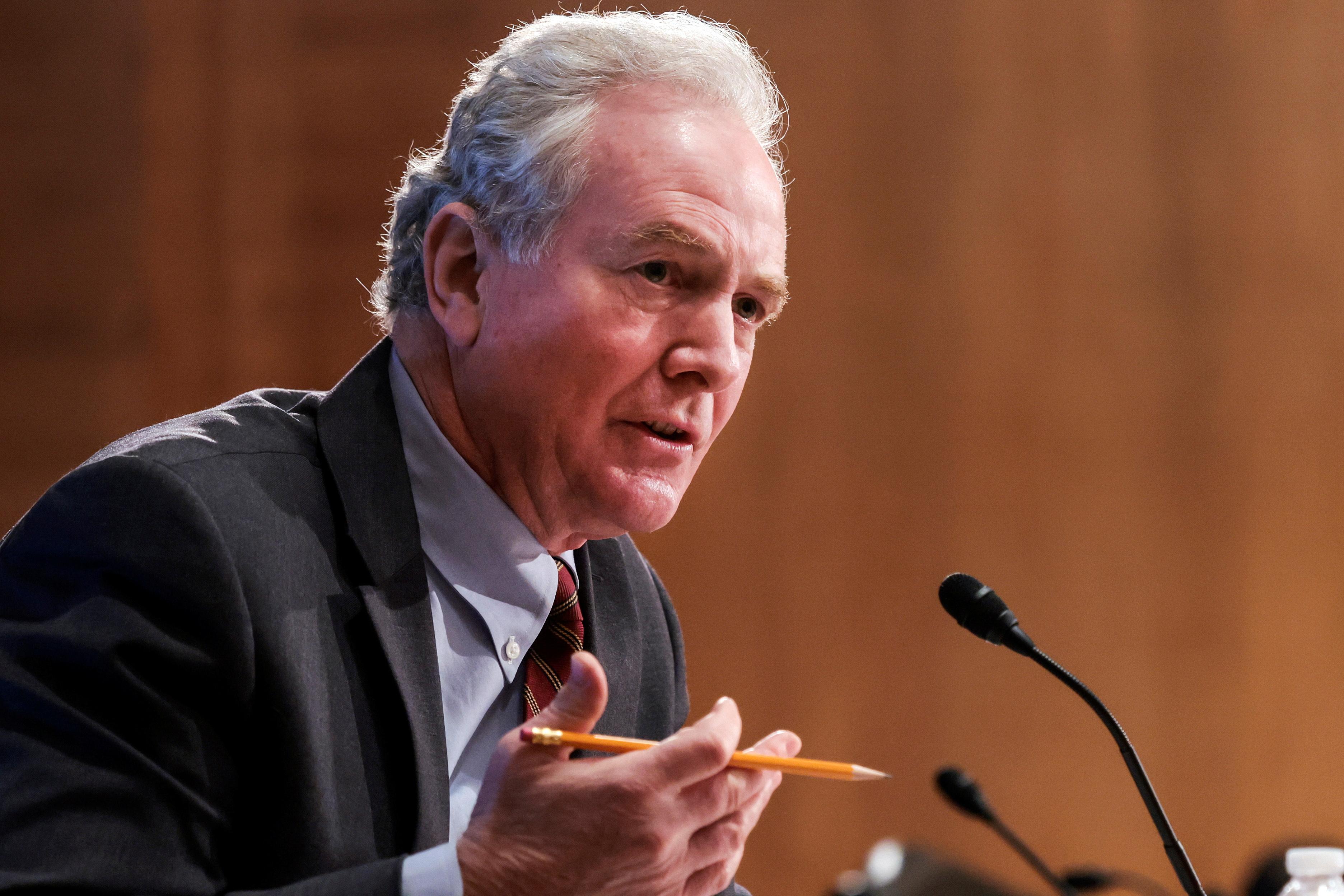

Senator Chris Van Hollen’s recent trip to El Salvador has ignited a firestorm of debate, with accusations ranging from a Logan Act violation to outright treason. The controversy stems from his meetings with Salvadoran officials, including discussions on U.S. foreign policy and El Salvador’s domestic affairs. Critics argue that Van Hollen, as a sitting U.S. senator, overstepped his authority by engaging in unauthorized diplomacy, while supporters claim he was fulfilling his oversight role. The truth lies in a complex interplay of law, politics, and international relations.

The Logan Act, a 1799 statute, prohibits U.S. citizens from conducting unauthorized correspondence or intercourse with foreign governments to influence their conduct in disputes with the United States. Violators face fines or imprisonment, though the law has rarely been enforced. Critics of Van Hollen assert that his discussions with Salvadoran leaders, particularly on issues like immigration and security cooperation, violated this act. They argue that his actions undermined the executive branch’s authority to conduct foreign policy, especially given reported tensions between the Biden administration and El Salvador’s leadership. Some even escalate the charge to treason, citing Article III, Section 3 of the Constitution, which defines treason as levying war against the U.S. or aiding its enemies. However, this accusation appears hyperbolic, as El Salvador is not an enemy state, and Van Hollen’s actions do not meet the legal threshold for treason.

Supporters of the senator counter that his trip was a legitimate exercise of congressional oversight. As a member of the Senate Foreign Relations Committee, Van Hollen has a mandate to monitor U.S. foreign policy and engage with international counterparts. His visit included meetings to assess the impact of U.S. aid programs and discuss regional migration issues, topics well within his purview. Public statements from his office emphasize that the trip was coordinated with the State Department and aligned with U.S. diplomatic objectives. This framing casts the trip as routine senatorial fact-finding, not rogue diplomacy.

The controversy is further complicated by political motivations. Van Hollen’s critics, primarily from conservative circles, point to his progressive stance and vocal criticism of certain U.S. allies as evidence of disloyalty. Social media platforms like X have amplified these claims, with posts alleging he negotiated secretly with Salvadoran officials to undermine U.S. interests. Conversely, progressive voices defend him, accusing detractors of weaponizing the Logan Act to silence dissent. The polarized rhetoric obscures the legal nuances and fuels public confusion.

Ultimately, the Logan Act’s applicability remains questionable. Legal scholars note its vagueness and lack of precedent, suggesting prosecution is unlikely. Van Hollen’s trip, while perhaps diplomatically bold, aligns with congressional norms and lacks evidence of intent to subvert U.S. policy. Treason charges are even less credible, rooted more in political theater than constitutional reality. The controversy reflects deeper tensions over the role of Congress in foreign affairs and the boundaries of political discourse in a divided nation.