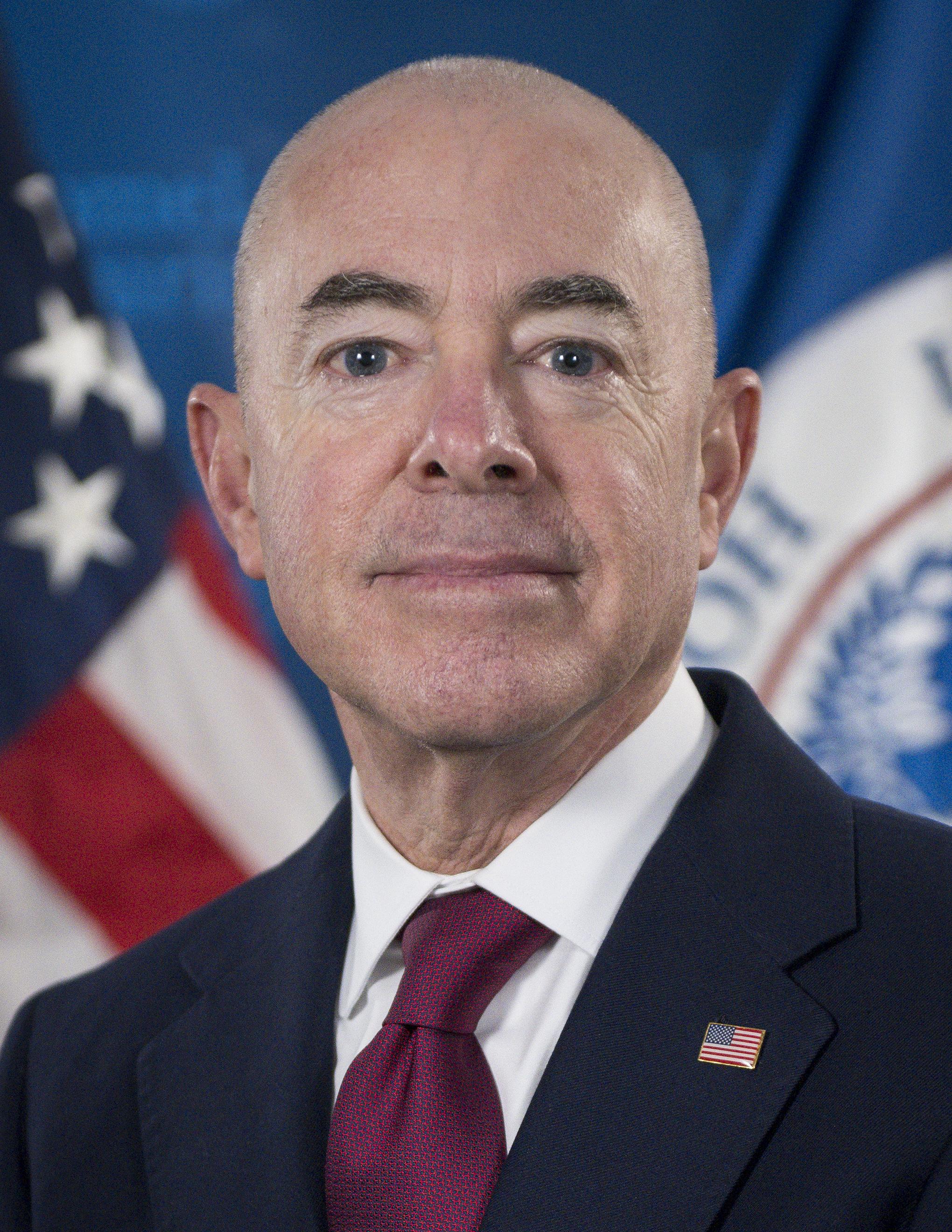

The ongoing immigration crisis at the United States southern border has ignited intense debates over accountability, national security, and the limits of executive authority. Central to this controversy is Secretary of Homeland Security Alejandro Mayorkas, whose tenure has faced mounting scrutiny from lawmakers, pundits, and the public alike. The question being posed more frequently now, especially by critics of the Biden administration, is whether it is time to arrest Mayorkas over his role in what they view as a gross mishandling—or even willful negligence—of U.S. immigration laws. But such a question raises not only political and ethical dilemmas, but also serious constitutional and legal implications.

To consider the arrest of a sitting Cabinet official is to venture into highly uncommon, if not unprecedented, territory. The United States system of governance is designed to allow for checks and balances between branches, with impeachment and congressional oversight acting as primary tools for addressing misconduct. Arrest, on the other hand, is a criminal procedure that demands a high burden of proof and due process. Therefore, the very notion of arresting Mayorkas should first be examined through the lens of legality. Has he broken the law? Has he committed an act so egregious that criminal prosecution is warranted?

Critics argue that Mayorkas has violated his oath of office by failing to enforce immigration laws passed by Congress. They point to record numbers of illegal crossings, the rolling back of Trump-era border policies, and what they see as an open-border approach that encourages unlawful entry. They allege that his policies have not only strained federal resources but have created humanitarian crises in both border communities and major U.S. cities where migrants are being transported. Some Republicans in Congress have even attempted to impeach Mayorkas, accusing him of “willful and systemic refusal to comply with the law.”

Supporters of Mayorkas, however, argue that the situation at the border is a reflection of decades-long dysfunction in U.S. immigration policy, exacerbated by global instability and economic inequality—not the result of one individual’s decisions. They emphasize that Mayorkas has operated within the boundaries of executive discretion, responding to an overwhelming influx of migrants with policies aimed at balancing security with humanitarian obligations. Furthermore, they stress that immigration enforcement is not simply about deportations and deterrents; it involves complex coordination with international partners, processing asylum claims under U.S. and international law, and managing resources in an unpredictable global context.

The call for Mayorkas’s arrest must also be scrutinized for its political motivations. In an era where partisanship often eclipses policy substance, demands for punitive measures against political opponents can serve more as symbolic acts than actionable legal strategies. Arresting a Cabinet official would likely be seen by many as an authoritarian overreach, a breach of democratic norms that could set a dangerous precedent. If a future administration were to arrest officials from a previous administration for policy decisions, it could unravel the foundational principle of peaceful transitions of power and mutual respect for institutional roles.

Moreover, law enforcement agencies, including the Department of Justice and the FBI, operate under strict guidelines about whom they can investigate and on what basis. The bar for criminal charges is significantly higher than that for political disapproval. While negligence or poor performance may warrant calls for resignation or impeachment, they do not automatically constitute criminal behavior. To date, there has been no credible evidence presented in court or in oversight hearings that Mayorkas has personally committed a crime or abused his authority in a manner that would justify arrest.

Another dimension worth considering is the message such an arrest would send internationally. The United States positions itself as a global leader in democracy, rule of law, and civil liberties. Using criminal prosecution to address policy disagreements would undercut that image and provide ammunition to authoritarian regimes who routinely jail political opponents under the guise of law enforcement. It would mark a perilous shift in how the U.S. handles internal political conflict and could fundamentally alter the relationship between the executive branch and its oversight mechanisms.

Still, the frustration felt by many Americans over the immigration crisis is real. The border situation has become unsustainable for some communities, and the sense of lawlessness undermines public confidence in the government’s ability to maintain order. But addressing these grievances must come through democratic processes—elections, legislation, and lawful oversight—not through what would appear as retaliatory justice. Holding officials accountable is vital in a functioning democracy, but accountability must be grounded in legal frameworks and not driven by outrage or political pressure.

In conclusion, while it is entirely valid for citizens and lawmakers to question Alejandro Mayorkas’s leadership during a time of crisis, the notion of arresting him steps far outside the bounds of lawful and rational response. A more constructive path forward lies in legislative reform, comprehensive immigration policy debate, and, if necessary, congressional actions that respect constitutional processes. The solution to a systemic problem is not scapegoating one man, but rather demanding effective governance across the board.